Second Reading of the Crime and Policing Bill in the House of Lords, which includes an abortion up to birth clause that was added in the Commons, took place on Thursday 16 October, with almost two-thirds of Peers who took a position on the abortion clause speaking against it.

Throughout the debate, of the 20 Peers who took a stance on the amendment, 13 (65%) spoke in opposition and 7 (35%) spoke in favour.

The abortion up to birth clause (191) was introduced by Tonia Antoniazzi MP in the Commons after just 46 minutes of backbench debate – there was no prior consultation with the public, no Committee Stage scrutiny and no evidence sessions.

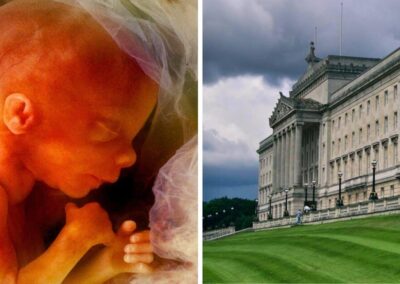

The clause would change the law so it would no longer be illegal for women to perform their own abortions for any reason, including sex-selective purposes, and at any point up to and during birth, likely leading to a significant increase in the number of women performing dangerous late-term abortions at home.

Two high-profile members of the House of Lords, Baroness Monckton and Baroness Stroud, have both tabled amendments with other Peers in the House of Lords to overturn the highly controversial abortion up to birth clause in the Crime and Policing Bill, and to reinstate in-person consultations with a medical professional prior to an abortion taking place at home.

Women’s safety a key concern in late-term unsupervised abortions

One of the key issues that presented itself throughout the debate concerned how women’s safety would be put at risk by late-term abortions permitted by clause 191.

Baroness O’Loan warned that the clause “constitutes a very significant change to our law on abortion” and “carries with it enormous risks to women” who might think that ending a pregnancy up to birth without medical help is safe, if the criminal penalty were to disappear.

Quoting Dr Caroline Johnson MP, a paediatrician, she highlighted that babies at 30 weeks gestation and upwards “have a more than 98% chance of survival”.

Baroness O’Loan continued by spelling out exactly how late-term abortions are carried out, by inducing cardiac arrest in the unborn child.

This theme was reiterated in a fierce speech by Baroness Monckton, who highlighted that late-term at-home abortions will likely create “a modern-day equivalent of back-street abortion”, leaving the door wide open for coercion to take place. “There is no popular demand or pressure for this form of infanticide”, she said.

She drew attention to the dangerous ‘pills by post’ scheme, which allows women to have abortion pills sent to their home without ever having an in-person consultation with a medical professional.

“I fear there would be an increase in the number of late-term abortions with no medical supervision whatever, particularly as women continue to be able to obtain pills through the post without an in-person consultation”, she said.

“That came in during the special circumstances of the pandemic, but it has not been rescinded as it should be, even though we are no longer in such a health emergency”.

Baroness Monckton also underscored the risks and dangers associated with abortion pills generally.

“Recent figures show that 54,000 women were admitted to NHS hospitals in England for the treatment of complications arising from the use of such abortion pills—a 50% rise from the figures before the pandemic”.

She continued, “Analysis of accredited official statistics published by NHS England and the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities shows that one in 17 women self-managing their abortion at home were subsequently admitted for hospital treatment. This clause will scarcely improve that”.

Twisting parliamentary processes in order to pass abortion up to birth is “the beginning of a slippery slope”

Lord Frost pointed out that the amendment, which would introduce “the biggest change to abortion legislation since the Act was introduced in 1967”, received insufficient scrutiny in the House of Commons. He highlighted that this would be “the beginning of a slippery slope”, and received only “a wholly inadequate couple of hours’ debate in the Commons”.

Lord Frost argued that there is no public demand for such legislation; indeed, he argued, the public supports the opposite. “Polling shows that more than half the public favour keeping abortion after 24 weeks a criminal offence”, he said, “and only 1% of women support introducing abortion up to birth – and, in passing, 70% of women support a reduction in the time limit from 24 to 20 weeks”.

He continued by highlighting the contradiction in our law and our medical practices as a society that such an amendment would bring.

“In our country, if children are born prematurely after 24 weeks, the medical system will do everything it can to save them, and it is often successful”, Lord Frost said.

“Yet this clause will make it possible to try to end the life of a baby after 24 weeks without criminal consequences. It is simply inconsistent, not just with current abortion law but with current law around maternal and child health more broadly”.

Lord Elliott of Mickle Fell stated that clause 191, which would decriminalise abortion up to birth for women in relation to their own pregnancies, “clearly marks a significant shift in the law on abortion in the UK”. Lord Elliott drew comparisons between the rushed treatment of processes of Kim Leadbeater’s assisted suicide Bill and the abortion up to birth amendment in the Crime and Policing Bill, saying, “If the assisted dying Bill has not been sufficiently scrutinised, as many have suggested, clearly the scrutiny of clause 191 is insufficient”.

He drew attention to a Written Parliamentary Question by Baroness Foster of Aghadrumsee, which asked the Government “what assessment they have made of the potential risks to vulnerable women, including those who may be subject to coercion or abuse, if abortion were to be decriminalised; and what safeguarding measures they plan to put in place to protect them”.

The Government, unfortunately, replied, “No assessment has been made”.

Lord Jackson of Peterborough agreed with this point, adding that the amendment, which “was added on Report in the other place without due consideration and with only 46 minutes of backbench debate”, is “unnecessary, badly drafted and will harm women”.

“Clause 191 is an embarrassment to supporters of abortion and a stain on our reputation as a country that claims to care for pregnant women and their unborn children”, he said.

Baroness Monckton reiterated that “just 46 minutes of backbench debate” is not sufficient time for proper scrutiny.

“Many MPs wanting to speak were unable to; this is not a responsible way to make law”, she continued.

Baroness Lawlor argued that clause 191 is wrong in both form and substance. It uses a private Member’s conscience amendment to amend a government Bill and then creates an inconsistency in the criminal law.

“First, a private Member’s conscience amendment has been used to amend a government Bill, bringing the weight of the Executive to a matter of conscience. Moreover, by this procedure, a matter of great significance may be allowed to slip through, tagged on to the Crime and Policing Bill, avoiding the full national and parliamentary scrutiny that such major changes in a law require”.

Baroness Lawlor continued, stating that such an amendment “goes against the very principle of law”.

“It is bad in principle and practice to count some action as a crime for some people but not for others. In clause 191, it is accepted that aborting a baby over 24 weeks old is normally a crime and that those involved should be punished, except for one—the pregnant woman who is the instigator of the action. Part of the very principle of what it is to be a law is that it is applied universally”, she said.

“Moreover”, she continued, “there could be no greater denigration of pregnant women, and indeed all women, than to deny them the most basic right of all: to be judged morally and, when they have committed a crime, judged criminally. Abortion over 28 weeks is accepted as a crime by all”.

“To say that pregnant women can commit it so long as they do so against their own children or own child—but nevertheless they are not criminals—is to treat them as less than fully human adults”.

Peers highlighted how there is no meaningful difference between a child during the late stages of pregnancy and once it has been born

Viscount Hailsham, who described himself as being a “strong supporter” of the 1967 Abortion Act, argued that this amendment to decriminalise abortion up to birth “goes far too far”.

“I find it very difficult to distinguish in principle between a child who has just been born and a child who is about to be born. If the child were killed immediately after birth, its killing would be an act of homicide; so, I suggest, is the killing of an unborn child immediately before its birth. There is very little distinction in principle”, he said.

Former Ofsted Chief Inspector Baroness Spielman was forthright that abortion cannot be reduced to a single patient’s healthcare. “It is blindingly clear that abortion is a profoundly difficult issue, because the rights attaching to two different lives conflict: this is why it figures in criminal law”, she said.

Baroness Spielman continued, stating that passing this amendment, which would allow women to have abortions up to birth, is akin to “giving women an unqualified right to kill their own children”.

“For abortion, there is an uncomfortable asymmetry: unlike their mothers, unborn children are helpless and voiceless. We should therefore reject the argument that abortion should be considered purely as a healthcare matter”, she said.

She continued, “Of course women’s healthcare matters, but to make healthcare the only consideration is to deny a vast and important ethical debate. Both lives in question matter very much”.

Lord Jackson of Peterborough also argued this point, stating that, as a result of this amendment, “[t]he humanity of the baby in the womb is ignored”.

Lord Jackson criticised this amendment, stating, “A wanted child is a baby and should be protected; an unwanted child is a foetus—an othering word, if ever there was one—and can be removed and disposed of”.

“I simply do not believe the degree to which a mother wants or does not want her baby changes the moral status of the child and think we need to have a national conversation about this”.

Abortion up to birth would shred a “vital protection” from coercion

Lord Farmer argued that clause 191 undermines the Crime and Policing Bill’s broader aim of protecting women and girls, through making it easier for coercive abuse to occur.

“Clause 191 shreds a woman’s criminal responsibility and, with it, a vital protection for her against a partner or family member coercing or predating on her to have a late-term abortion. Bringing about her own late-stage termination of a baby that has been kicking, hiccupping and otherwise moving in utero will leave a long tail of effects on her life”.

“Decriminalisation is only caring and compassionate in a very narrow and short-term way. This House will discuss ramifications of allowing terminations up to birth, but the only fit place for clause 191 is the cutting room floor”.

Lord Farmer continued, arguing that abortion “is treated as an unlimited good in our topsy-turvy moral universe”.

“Whatever we individually think about abortion, the laws of this land and a wide range of other considerations are being ignored or twisted out of shape to meet the insatiability of extreme bodily autonomy”, he argued.