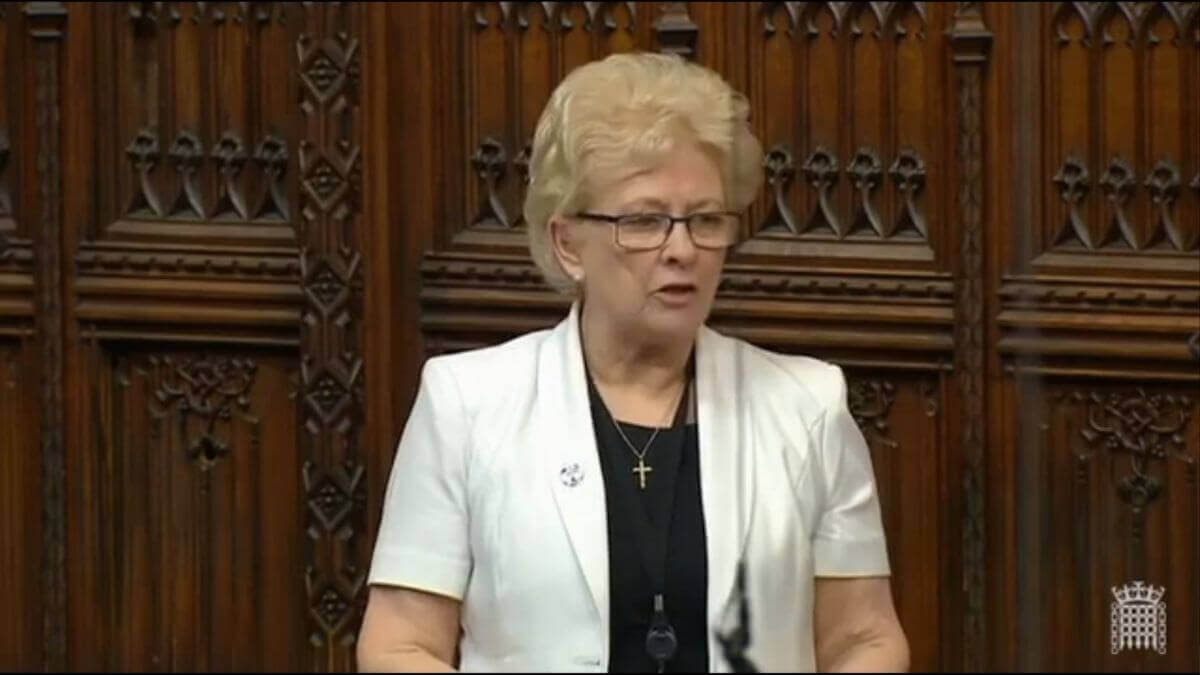

Member of the House of Lords, Baroness O’Loan, has strongly condemned Tuesday’s abortion vote in the House of Commons as being “reminiscent of colonial days” as it undermined the sovereignty of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the people of Northern Ireland to make their own decisions about their own abortion law.

On Tuesday evening, an amendment was added to the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation) Bill – a Bill designed to extend the period for forming an Executive in Northern Ireland – which attempted to introduce extreme changes to abortion law in Northern Ireland. The debate continued on Wednesday in the House of Lords with the second reading of the Bill and the new abortion amendment were heavily criticised by a majority of the of members the Lords who spoke.

Baroness O’Loan, who lost her own unborn baby as a result of an IRA bombing, criticised the amendment for its complete disregard for normal parliamentary procedure; for its undermining of the principle of devolution and for the fact that the potentially far-reaching consequences of the radical abortion proposals were not made clear to those voting on the issue.

Highlighting the sidestepping of parliamentary process to force through a controversial and wide ranging abortion amendment, O’Loan pointed out that:

“[T]here has been no White Paper, no Green Paper, no consideration of the impact of the provision, no consultation, no explanatory memorandum from [Stella Creasy], no consideration of conflicting current legislative measures. There has been no provision even for this to be done with the proper parliamentary procedure through both Houses of Parliament…”

Neither was there any real “discussion in either Chamber of where medical science is in relation to the life of the unborn child, and no consideration of the pain which we know unborn babies suffer when they are aborted.”

In reference to the appeal made in the abortion amendment to The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Baroness O’Loan questioned why the British Parliament is forcing through an abortion amendment “at the behest of an unelected, unknown committee, operating under a complaints procedure contained in a protocol to a convention.”

Abortion is a devolved issue in Northern Ireland, which means it is up to the Assembly of Northern Ireland to make decisions on it for the region. The issue was most recently debated in 2016 where the majority of the Northern Ireland Assembly voted to keep the current protections for unborn life in law.

Yet O’Loan, in her scathing critique of the decision of 332 MP to impose the will of the Parliament in Westminster on Northern Ireland, said: “[T]here is no democracy now. Devolution has gone, in effect, on those occasions on which Parliament decides it wishes to act against it.”

Clare McCarthy of Right To Life UK said:

“Baroness O’Loan excellent and politically sensitive speech was right on every point. She was right to highlight the fact that normal parliamentary procedure, as well as public scrutiny and any regard to devolution, was completely disregarded in relation to an abortion amendment which could radically change the abortion law in Northern Ireland and even the rest of the UK.

“She was right to highlight the abuse of the role and power of the Speaker by selecting an amendment which has nothing to do with the Bill and potentially changing the law for the entirety of the UK.

“She was also right to point to the humanity of unborn children and the fact that protections for unborn life are not a form of oppression – two points which were largely not mentioned in a debate about forcing abortion of Northern Ireland”

***

Baroness O’Loan’s full speech is included below:

It is with a very heavy heart that I speak to noble Lords today. First, I would like to join those who have paid tribute to Sir Anthony Hart for his superb work and to express my sympathy to his family. We have lost a very distinguished public servant in Northern Ireland.

Being without a Government for two and a half years has been quite difficult for us. We are stuck. The consequences for our economy, which is now in decline, are well known. Our health service is struggling. Our education service, as noble Lords have pointed out, requires significant development and our past has not been dealt with in a coherent and constructive way. That is all well known.

There seems to be little evidence that the current negotiations will produce an Executive. We do not know what is being discussed at these purported negotiations; the signals are profoundly depressing. The Secretary of State told us yesterday that they have had 150 meetings, but they could not have the one that worked it out together.

There are hundreds of issues on which the parties could unite for the common good, and there is an urgent need for actions that could benefit our whole community and would not be contentious. Such actions would begin to heal some of the harm done in the past two and a half years when so much trust has been eroded in our democracy. Sinn Féin continues publicly to support the deeply anti-democratic campaign of murder by the Provisional IRA. It is deeply resented, not just by Unionism. In private conversations, we are receiving no assurances of any kind. The noble Lord, Lord Morrow, said that nothing is coming.

What happened yesterday in the other place was reminiscent of colonial days. The people of Northern Ireland are being denied the right the law accords them to make their own decisions in devolved matters. Through the amendments introduced yesterday, the other place has driven a coach and horses through the Good Friday agreement, which I would remind noble Lords is an international treaty binding on the United Kingdom. In addition, by doing this, the other place has given effect to the demands of Sinn Féin and taken a decision against the DUP. Others are saying that the DUP is very happy about this because it will not have to deal with those two issues. I have not heard noble Lords here or colleagues elsewhere express that view.

In imposing a deadline of 21 October for the negotiations to succeed, in the absence of which the Government will have to act in accordance with this Bill, the other place has taken away from the people of Northern Ireland their right to make their own decisions about matters which in law are devolved to them. They have acted in a partisan manner.

It is not that devolved powers have been withdrawn from Northern Ireland; they will exist in parallel with this Bill. In continuing to present this Bill—of course, the Government could withdraw it—the Government have made it much more unlikely that Sinn Féin will come to the table with open hearts and willing minds. It does not need to do so. It can just sit and wait until the Members of the other place do the work for it. As a consequence of the other place passing these amendments, Sinn Féin does not have to engage in democracy to achieve its ends; it can just say, “We refused to engage and look what happens”.

In 1967, the Parliament of Northern Ireland voted against embracing the Abortion Act. In 2016, the Northern Ireland Assembly, as noble Lords have heard today, voted by a clear majority not to change our abortion law in any way. The Government have consistently given assurances to the people of Northern Ireland that the devolution provisions will be respected. On 30 October last, I pointed out that in June of that year, the noble Lord, Lord O’Shaughnessy, gave me an assurance that the intention of the Government and the NIO,

“is to restore a power-sharing agreement and arrangement in Northern Ireland so that it will be up to the people of Northern Ireland and their elected officials to decide on abortion policy”.—[Official Report, 6/6/18; col. 1312.]

In October 2018, the Minister said:

“As someone who comes from part of the kingdom which has a fully functioning devolved Government, I stress again that these decisions must be taken by the devolved Administration in the north of Ireland. There is no point in pretending we can usurp democracy in that fashion, simply because devolution is not to our liking. Devolution must function even when it is not as we would like to see it, but rather, how it must be”.—[Official Report, 30/10/18; col. 1278.]

As the noble Lord, Lord Alton, said, until last week we did not know what would be in the amendment. We had intimations that it might be coming, but the first we saw of the Creasy amendment was on Thursday morning last. Within hours, it had been passed by the House of Commons. The expectation was that the Speaker would do the right thing and exclude it because it was outside the scope of the Bill. The transparent inappropriateness of this was further underlined by the fact that—entirely consistent with the vote by the democratically elected Northern Ireland Assembly in 2016—100% of our MPs voted against the provision. It was imposed on us by more than 300 MPs who have neither consulted us nor represent us.

If we meddle in the affairs of Northern Ireland in this heedless way; if we do not object to the House of Commons introducing clauses which have nothing to do with the Bill before the House; if we accept that the Government have lost control of Parliament; if Parliament allows one person—the Speaker of the other place—to make his own decisions about what can and cannot become law, without having regard to international treaty obligations such as those which derive from the Good Friday agreement, human rights law and even the domestic law of the United Kingdom, we are surrendering our democracy and our much cherished constitution. For Northern Ireland, with 17 MPs in a Chamber of 600-plus, there is no democracy now. Devolution has gone, in effect, on those occasions on which Parliament decides it wishes to act against it.

The Select Committee on the constitution of your Lordships’ House, in a paper published just nine days ago, entitled The Legislative Process: the Passage of Bills through Parliament, stated at paragraph 39:

“We regret that legislation relating to Northern Ireland has regularly been fast-tracked. This has become common not just for bills which might be required to address urgent or unforeseen problems, but for routine and predictable matters such as budgetary measures. The political stalemate in Northern Ireland has led to an absence of a functioning Executive and a democratic deficit. Fast-tracking bills relating to Northern Ireland reduces further the scrutiny these measures should receive. Routinely fast-tracking in this way is unacceptable, unsustainable and should only be used for urgent matters”.

I have no doubt that the ultimate purpose of these amendments is to change Northern Ireland and UK law by decriminalising abortion. I know that many of your Lordships will have a different view on abortion from me, and I accept that, but that is not actually the point today. Clause 9 would mean that abortion would cease to be subject to any penalty in all circumstances. That means that any baby, at any stage of gestation, right up to birth, could be aborted without penalty. As the noble Lord, Lord Alton, said, there is no human right to kill unborn babies.

I believe, as do hundreds and thousands of others, that human life exists from the moment of conception and that it should be protected at all times. Even those who are pro-choice are now beginning to accept that abortion is about killing babies. If you are three or five months pregnant and you go for a scan, the radiographer does not say to you, “That’s your foetus” or “That’s your embryo”. They say to you, “That’s your baby”. When I lost my baby, as the consequence of a bomb explosion, the doctor who stood at the end of my bed did not say to me, “Your pregnancy is over”. He said to me, “Your baby is dead”.

I will say a word to the noble Baroness, Lady Harris. I reassure her that neither I nor hundreds of thousands of people in Northern Ireland feel oppressed, down- rodden or deprived of equality—far from it. We think that our law brings freedom to mothers and their children, and we seek to support them. I spoke in Oxford just a couple of weeks ago on freedom of conscience, and at the end of it, a woman came up to me. She said that she had recently carried a baby who had Down’s syndrome, and at each of her prenatal visits, the doctor had said to her, “You know it would be much easier—you could have an abortion. You should have an abortion”. It was a constant message, right through her pregnancy—a time when women are most vulnerable.

Let us be very clear. Clause 9 would change the law in England and Wales. The Member for Walthamstow said in the other place in June last year

“We would like to repeal sections 58 and 59 of OAPA”.—[Official Report, Commons, 5/6/18; col. 207.]

Those are the penalty provisions of the Offences against the Person Act. This clause will override not just the expressed will of the last democratically elected Northern Ireland Assembly but the deliberations of this Parliament.

I do not believe that those who voted as they did in the other place yesterday really intended to abolish any penalty for unlawful abortion in the UK, yet that would be the effect. If we decriminalise abortion—that is what this amendment seeks to do—we will make abortion available up to birth. I do not know how many of your Lordships have known the beauty and the terror of the moment of birth: the moment when a new soul, a beautiful little baby, comes into the world. It is a moment of absolute wonder. I accept that there are occasions when women do not want to carry their babies to term, but we need to be very clear that abortion is not a painless, clean, medical process. A baby will be killed in the womb through medication, have poison injected into its heart so that it is born dead, or it might just be born alive, as are an average of 30 babies each year in England and Wales, and left to die. In that brave new world, there will be fewer and fewer children with disabilities, as they do not merit the right to life. According to the Bill before your Lordships’ House, children with disabilities will be given no protection. Yet we know that while children may be born with disabilities, that is not the sum total of the reality of their existence; they deserve more than to be defined by their disability.

In England and Wales, we abort children because they are the wrong sex—we have proof of it—and because they have conditions like club feet and cleft palates, which are eminently curable. In effect, we have abortion on demand up to 24 weeks, and we will have abortion to birth. What sort of civilisation would countenance the killing of defenceless, unborn babies in the place where they should be safest: the mother’s womb? What sort of civilisation does this right up to the moment a baby is born?

Reverting to parliamentary procedure, there has been no White Paper, no Green Paper, no consideration of the impact of the provision, no consultation, no explanatory memorandum from the Member for Walthamstow, no consideration of conflicting current legislative measures. There has been no provision even for this to be done with the proper parliamentary procedure through both Houses of Parliament, rather than a Statutory Instrument subject only to negative resolution, which is all that would be required—the least accountable form of legislation. There will be no discussion in either Chamber of where medical science is in relation to the life of the unborn child, and no consideration of the pain which we know unborn babies suffer when they are aborted. There has been no thought of what we are saying as a people when we force this measure through at the behest of an unelected, unknown committee, operating under a complaints procedure contained in a protocol to a convention.

The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly stated that states have a margin of appreciation in these matters: we have the right not to do this and we should not do it. Yet, this is what the other place has determined will dictate our future law, not proper parliamentary process, not even decisions influenced by the finest legal minds in the country making decisions in our Supreme Court, with the protections afforded by our resolute application of the rule of law. It is profoundly and fundamentally wrong that we should agree to consent to the disposal of human life before birth by means of a measure that was designed only to extend the period for forming an Executive in Northern Ireland until 21 October, and to grant powers to the Secretary of State to extend the period to 13 January 2020. We must reject this in Committee; if we do not, Northern Ireland will have had abortion foisted on it at a time of political crisis by the Parliament of a country that has some responsibility for what has happened to it in the past. There are those who are seeking to inflict on us more troubles. We have seen the bombing attempts. Last night, we saw the problems at bonfires as we approach 12 July—environmental problems that nevertheless resulted in rather more serious problems. Many of us still live in fear, and it is not an irrational fear. We have huge problems, with marginalised, impoverished and deprived people living in bleak conditions, where the rule of the terrorists still operates. Let us be under no illusion: the rule of the terrorists still operates in Northern Ireland.

It seems to me that despite the best efforts of the Minister and all those concerned, the Government have stood by and done very little for the past two and a half years. It will be worse if we acquiesce in this travesty of a Bill, containing a clause imposing abortion on demand on a people who have repeatedly said they do not want it.