Former paralympian, Baroness Grey-Thompson, has criticised the Government for encouraging the assisted suicide of those with disabling conditions.

This week, the House of Lords debated the impact of Covid-19 regulations on the ability of British citizens to seek assisted suicide or euthanasia abroad, as well as the legal position of family members who accompany them.

In a follow-up to last Thursday’s Urgent Question in the Commons from Andrew Mitchell MP on the same subject, the Government reiterated that, while the assistance or encouragement of suicide remains illegal in this country, it is still permissible to travel abroad for the purposes of assisted suicide during the current crisis.

In his statement to the House, the Health Minister Lord Bethell acknowledged that seeking assisted suicide has been considered a ‘reasonable excuse’ for foreign travel.

However, he also reaffirmed that Section 2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961 penalises anyone who ‘does an act capable of encouraging or assisting the suicide or attempted suicide of another person’, if that act ‘was intended to encourage or assist suicide or an attempt at suicide’.

The Government stressed that ‘there is nothing in the Coronavirus Act or any recent legislation that in any way changes that.’

In a reply to a written question on the subject the day before the Lords’ debate, the Government confirmed that there remain ‘no plans to review the law on assisted suicide or issue a call for evidence’.

Lord Bethell equally emphasised that the Director of Public Prosecutions previously updated their guidelines governing such cases, which identified ‘public interest factors tending against prosecution’ including the motivation of assistance by compassion.

Despite repeated complaints from assisted suicide advocates over the dangers of prosecution, there have only been three cases of prosecution for assisting or encouraging suicide since April 2009 of the 162 cases referred to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Encouraging the assisted suicide of people with disabilities

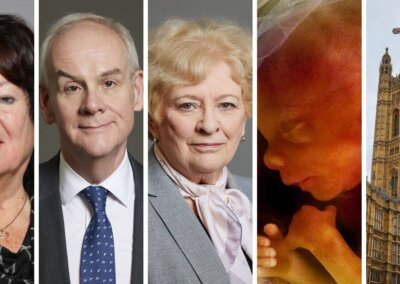

During the debate, former Paralympian Baroness Grey-Thompson criticised the Government for encouraging the assisted suicide of people with disabilities.

She was joined by Baroness Stuart who argued that such travel guidance for assisted suicide is deeply inappropriate at a time of significant national sacrifice to protect the lives of the vulnerable, especially the elderly and infirm.

Baroness Grey-Thompson denounced the updated travel advice as ‘particularly inappropriate’ in the twenty-fifth anniversary year of the Disability Discrimination Act and the reported rise of mental health conditions following a diagnosis of Covid-19.

The former Paralympic athlete, who won 11 gold medals, four silver and one bronze, further critcised the Government’s response as it ‘encourages the suicide of those with disabling conditions’.

She drew attention to the significant impact of ‘the fear of being a burden, and other social factors’ on demand for assisted suicide in other countries. 1% of participants in a Washington state Department of Health report in 2018, for example, cited concerns that they would be a burden on their family, friends and caregivers, should they continue to live.

Health Secretary did not seek advice from the Director of Public Prosecutions

Baroness Grey-Thompson’s question also revealed that the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Matt Hancock, did not seek any advice from the Director of Public Prosecutions in relation to the official guidance.

While Lord Bethell noted that the Government technically did not change the law, Baroness Stuart insisted the Government’s statement ‘goes further than just travel advice’ to ‘create a presumption that people at the end of life only have the option to travel abroad’.

Questioning whether such advice was truly ‘the right decision’, Baroness Stuart reminded her fellow Members of how ‘many people in care homes would seek the companionship of members of their families but [currently] forego it in the wider community interest’.

Central to Baroness Stuart’s contribution was the importance of palliative care for those approaching the end of life. She argued that ‘[s]urely more palliative care and more focus on helping people to a good death are more important during this Covid crisis than facilitating people to travel abroad’.

Although the Health Minister Lord Bethell acknowledged that palliative care has been ‘an incredibly important part of the Covid crisis’ and provided ‘huge succour, compassion and care for those at the end of their life’, those involved with end of life care have said that more needs to be done to support end of life care in this country.

According to Hospice UK, 93% of hospice care leaders are concerned that patients with vital end-of-life care needs could miss out on essential support through lack of resources.

Not a single doctors’ group or major disability rights organisation in the UK supports changing the law, including the British Medical Association (BMA), the Royal College of General Practitioners, the Royal College of Physicians, the British Geriatric Society and the Association for Palliative Medicine.

Right To Life UK spokesperson Catherine Robinson said: “We must commit to improving the state of palliative care in this country. Such investment is essential to underline the common human dignity and equality of all, not least the elderly and infirm.

These values are foundational to any society, but also fragile and in need of protection. Our society must avoid neglecting those who can no longer contribute as much economic value, and embrace our interdependence by championing needed palliative care for the elderly and infirm.

What can be more compassionate than confirming to our vulnerable fellow citizens that their lives are always worth living?”